An article from HRSA (Health Resources & Services Administration)

Commwell Health of Dunn, N.C. serves some 25,000 patients in six counties south of Raleigh. It has been providing HIV screening since 1990 and became a Ryan White grantee in 1998 — making it one of the oldest community-based primary HIV care practices in the state. The SPNS Team, from left: Chief Behavioral Health Officer Janet Stroughton, with Michaella Kosia, Lisa McKeithan, Bahby Banks, Mirna Allende, Shalonda Pellam and Stephanie Atkinson.” “A lot of our patients were living in cars. They were couch-surfing. They literally had no place to live.”

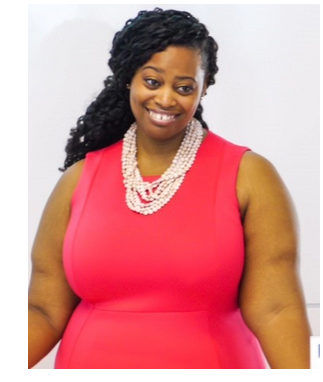

Lisa McKeithan of Commwell Health in Dunn, N.C., was momentarily overwhelmed describing her team’s work with itinerant patients. The HRSA-funded rural health center was one of the nine grantees in the SPNS homelessness initiative.

Homeless adults living with HIV — and further stressed with mental illness or substance abuse — have long been much harder to keep in care than the broader HIV-positive population of some 1.1 million Americans, half of whom receive health services through HRSA-funded Ryan White clinics nationwide. But their success rate markedly increases when they are adequately housed, results from a HRSA HIV/AIDS Bureau (HAB) outreach project show.

Moreover, by “taking the clinic where they are” — in converted buses, if necessary, as a Yale University team showed — people without a home can get the regular treatment they need to keep their HIV and other disorders in check, nine grantees involved in the project report.

In one of the most hopeful advances in years, HIV viral suppression rates have increased from 69 to 83 percent among patients “who walk through the door to get health care at least once in a year,” said Dr. Laura Cheever. Associate Administrator of the HIV/AIDS Bureau and a practicing Johns Hopkins clinician, she addressed researchers on June 27 at HRSA headquarters.

Special Projects of National Significance are funded through HRSA’s Ryan White program and provide care to some 8,700 patients at high risk of dropping out of treatment. The program also seeks to pioneer new methods — including the use of social media — to increase service integration and expand the population of patients who are virally suppressed. From left, Adan Cajina, SPNS Supervisory Health Scientist; HAB Associate Administrator Dr. Laura Cheever; and long-time SPNS Health Scientist Jessica Xavier spoke with grantees at a conference on homeless patients on June 27. A second meeting the next day focused on ways to better serve transgender women of color.”>

But people experiencing homelessness have rates of new infection as high as 16 times that of the general population.

5-year SPNS project overseen by Boston University was to find ways to reduce the infection rate and barriers to care among more than 1,300 homeless patients with HIV and co-occurring disorders in eight major American cities, from New Haven and Jacksonville to Portland, Ore. and San Diego, and in six largely rural counties outside Raleigh, N.C.

In so doing, they broke new ground.

Employing networks of street-level navigators, linked to community partners — from health care providers to landlords — researchers sought out chronically homeless, hard-to-find, marginalized people, said Serena Rajabiun of Boston University, in a kind of “mobile medical home.”

Communicating in e-mail “huddles,” by cell phones, text-messaging and landlines, teams created open access clinics that linked primary and behavioral health care, grantee officials said — including big blue buses roving the streets of New Haven.

“They moved beyond the clinic walls,” Rajabiun said, with a case manager heading each team.

The people they found — on the streets of Dallas and Houston; Pasadena and San Francisco — were chronically disadvantaged: 62 percent were homeless; 33 percent hadn’t had medical care in six months or more; about a third were “unstably housed,” at least a dozen were fleeing domestic violence and more than four in 10 had experienced sexual assault or physical injury.

Among the most common problems: 75 percent had a mental health condition, in addition to HIV.

“We’re seeing some increase in retention in care and viral suppression rates, even among people who are still experiencing homelessness,” Rajabiun reported. “We are seeing a reduction in unmet need in terms of substance use, mental health and housing.”

In particular, a study of more than 900 patients found them healthier and more likely to have a home one year after enrolling in the project.

The volume of homeless patients declined from 84 percent at the start of the project to 36 percent within 18 months. As it did, greater numbers received regular health care, she said.

Most importantly, rates of viral suppression increased from 51 to 82 percent in one year.

“We met them where they were,” said Maurice Evans, a navigator in Portland with the Multnomah County, Oregon Health Department HIV Health Services Center. “We treated them as human beings. We were able to form bonds and relationships with them — and they trusted us because we were leading them to where they wanted to go.”

Said Dr. Cheever: “You found the other people that we are desperately interested in … We have huge gaps in our knowledge about these people and how to effectively reach them,” which is the key to achieving further reductions in new infections and the spread of the disease.

Read the SPNS Fact Sheet (PDF – 356 KB) from HRSA’s HIV/AIDS Bureau.

Learn more about CommWell Health.

See a directory of SPNS initiatives underway by the University of San Francisco Center of Excellence for Transgender Health and its eight partner grantees.

Last Reviewed: July 2017